Diabetes and DR: Progress in a global epidemic

Clinicians' knowledge of the epidemiology, natural history, causal mechanisms, and treatments for diabetic retinopathy (DR) has evolved dramatically over recent decades.

Reviewed by Lloyd Paul Aiello, MD, PhD

The understanding of the epidemiology, natural history, causal mechanisms, and treatments for diabetic retinopathy (DR) has evolved dramatically over recent decades.

The staggering statistics underscore the importance of this progress considering that by 2040, an estimated 642 million patients will be affected by diabetes globally. Importantly, 7.3 million are undiagnosed and a third of the population is pre-diabetic, which, as Lloyd Paul Aiello, MD, PhD, noted, is a less recognized problem.

Aiello is a professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, and director, Beetham Eye Institute, Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston.

Demographics

“The percentages of diagnosed, undiagnosed, and total diabetes among adults increase dramatically with age, in some cases more than 7-fold between ages 18-44 and 65 and older,” Aiello said. “The incidence of diagnosed diabetes increases about 2-fold after age 40.”

Aiello explained further that about 20% of the US population over 65 years are projected to have diabetes by 2035. Diabetes currently is the seventh leading cause of death in the US.”

Black, non-Hispanic, and Hispanic populations have higher prevalence rates of diabetes than white, non-Hispanics. While diabetes about 20 years ago was far more prevalent in the southern US, it is now highly prevalent nationwide, with the rates having increased from 1.5%-6.9% in 2004 to 12.2%-33.0% currently.

High A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol, are well-known risks.

“A concern is that less than 20% of diabetic adults control these risk factors adequately and more than 75% do not adhere to minimal activity guidelines,” he said.

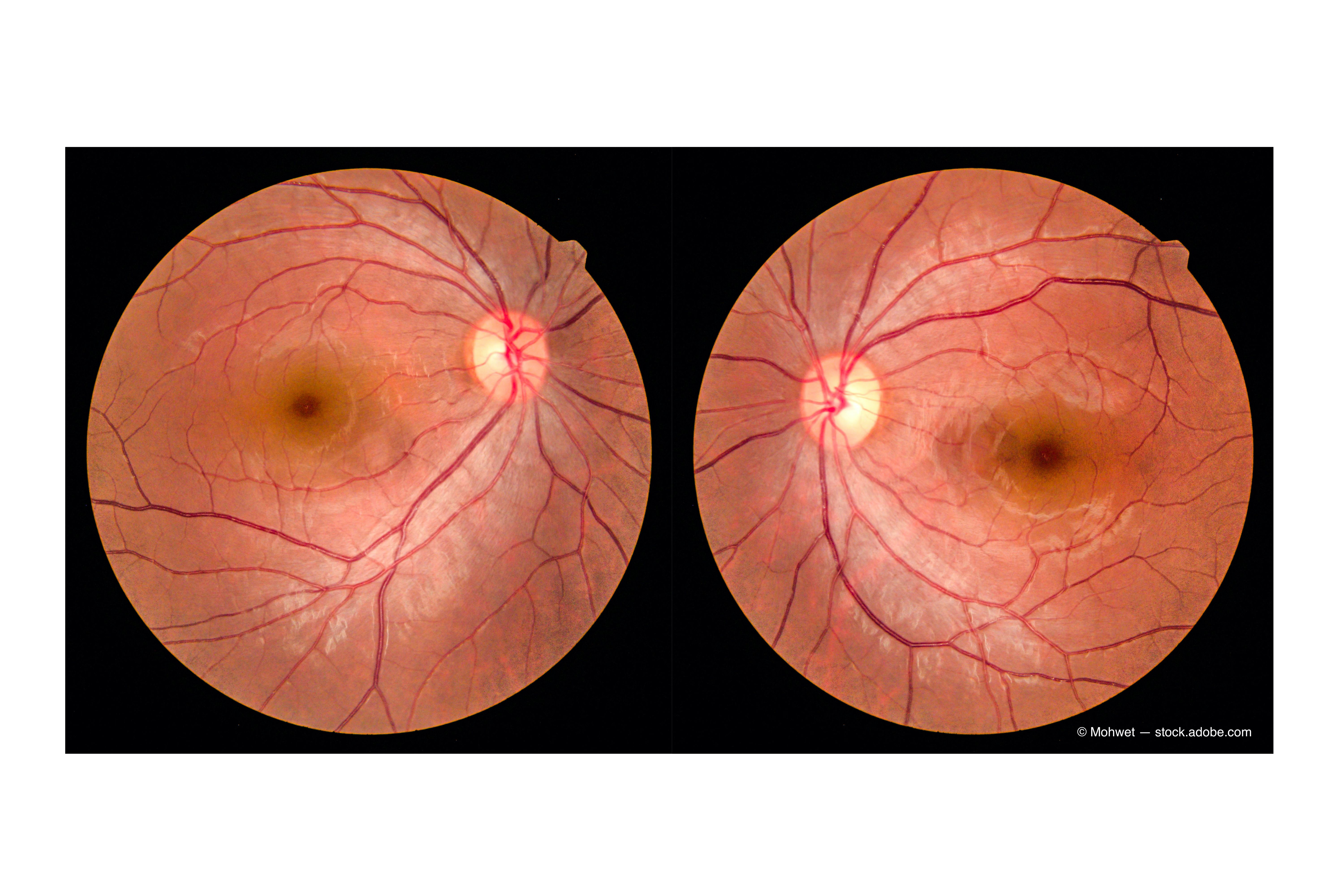

Emphasis on DR/DME

DR is one of the most common complication, with a prevalence of 49%; however, there is hope, because the cases of global blindness actually decreased slightly in Western Europe and high-income areas of North America possibly because of nationwide diabetic retinopathy screening programs in the UK, improved glycemic control, and better therapies,1 Aiello pointed out.

Decreases in diabetic macular edema (DME),2 proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), retinopathy progression, clinically significant ME, and visual impairment have occurred.3 Evaluation of about 15,000 patients at the Joslin Clinic showed a median best-corrected visual acuity (VA) of 20/20 and 92% had 20/40 or better.

In addition to improved diabetes care, treatment rates and better therapies also are credited for improved outcomes. Treatment with panretinal photocoagulation (PRP), which prevents about 98% of blindness when patients were treated in a timely fashion, increased substantially.

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy was a huge leap forward4 and is evolving as a viable alternative to PRP for PDR. Ranibizumab (Avastin, Genentech) was non-inferior to PRP, provided better vision during the first 2 years post-treatment and better mean visual field outcomes, and decreased chances of vitrectomy and developing DME.

Anti-VEGF therapy has been extremely effective for DME with study data now over 5 years.5 The major anti-VEGF drugs are all beneficial with somewhat similar efficacy except in certain subpopulations.6

Supplementation with deferred/prompt laser treatment helped maintain VA gains, and 56% never needed any laser over the 5-year study.5

Interestingly, while a number of anti-VEGF injections are needed in early treatment, far fewer are needed later on to maintain the visual gains.

A new therapeutic option is treatment of non-PDR. The Panorama Study7 showed high percentages of patients with 2 or more steps of improvement, lower rates of worsening in DR severity, and fewer vision-threatening complications from baseline with anti-VEGF therapy compared with sham.

In addition, the development of sophisticated imaging modalities is changing evaluation and treatment modalities and how diabetes-related eye disease is screened in the community.

A major hurdle for DR is the lack of patient awareness, which is a substantial contributor to non-adherence to eye care guidelines and poor outcomes, Aiello emphasized.

Retinal imaging is the best way to view almost the retinal surface with some devices now showing nearly the entire retina in a single image. Hand-held imaging devices are evolving and will likely help monitoring of patients in underserved areas.

The future of DR care may include several exciting new research areas. One is retinal binding protein 3 that may protect against many aspects of DR.8

In addition, there are pathways that do not depend on VEGF, and artificial intelligence and deep learning that are already entering the clinical arena.

Lloyd Paul Aiello, MD, PhD

E: LloydPaul.Aiello@joslin.harvard.edu

This article is adapted from Aiello’s presentation at the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology 2021 virtual annual meeting. He has no financial interest in this subject matter.

--

References

1. Liew G, Michaelides M, Bunce C. A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16-64 years), 1999-2000 with 2009-2010. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004015. Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004015.

2. Klein R, Knudtson MD, Lee KE, et al. The Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy XXIII: The twenty-five-year incidence of macular edema in persons with type 1 diabetes. Ophthalmology 2009;116:497-503.

3.Klein R, Klein BEK. Are individuals with diabetes seeing better? a long-term epidemiological perspective. Diabetes 2010; 59:1853-60. https://doi.org/10.2337/db09-1904.

4. Writing Committee for the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:2137-46.

5. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network, Elman MJ, Aiello LP, Beck RW, et al. Randomized trial evaluating ranibizumab plus prompt or deferred laser or triamcinolone plus prompt laser for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2010;117:1064-77.

6. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1193-203.

7. Wykoff CC. Intravitreal aflibercept for moderately severe to severe non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR): 2-year outcomes of the phase 3 PANORAMA Study. Data presented at: Angiogenesis, Exudation and Degeneration Annual Meeting; February 8, 2020; Miami, FL.

8. Yokomizo H, Maeda Y, Park K, et al. Retinol binding protein 3 is increased in the retina of patients with diabetes resistant to diabetic retinopathy. Sci Transl Med 2019;11:eaau6627. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau6627

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.