From intravitreal injections to gene therapy, new AMD treatments are on the horizon

Reducing the treatment burden is a prime goal for emerging AMD therapies.

Reviewed by Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA.

Retina is a rapidly evolving field. Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA, an associate professor of ophthalmology and surgical retina fellowship program director at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, recently shared some standout therapies for macular degeneration.

Dry age-related macular degeneration

There is no approved treatment for dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), but Weng is excited that that scenario is close to changing. Two hundred million individuals worldwide are affected by macular degeneration, most of whom have dry AMD and about 5 million of whom have the most advanced form of the disease, namely, geographic atrophy (GA). Clearly, a potential treatment is highly anticipated.

“Treatment of dry AMD and GA is perhaps the greatest unmet need in our field,” Weng said. “However, that is not for lack of trying.”

Dry AMD is an extremely complex disease that has been investigated from a number of different approaches. One of these, overactivation of the complement cascade, has become a target of therapeutic interest, she explained.

Focus on 2 molecules

Two molecules are of special interest in late-stage clinical trials. One of the molecules, pegcetacoplan, blocks at the level of C3 in the cascade. C3 is the point of convergence of all 3 complement pathways, ie, alternative, classical, and lectin. The second molecule, avacincaptad pegol, works farther downstream and blocks at the level of C5.

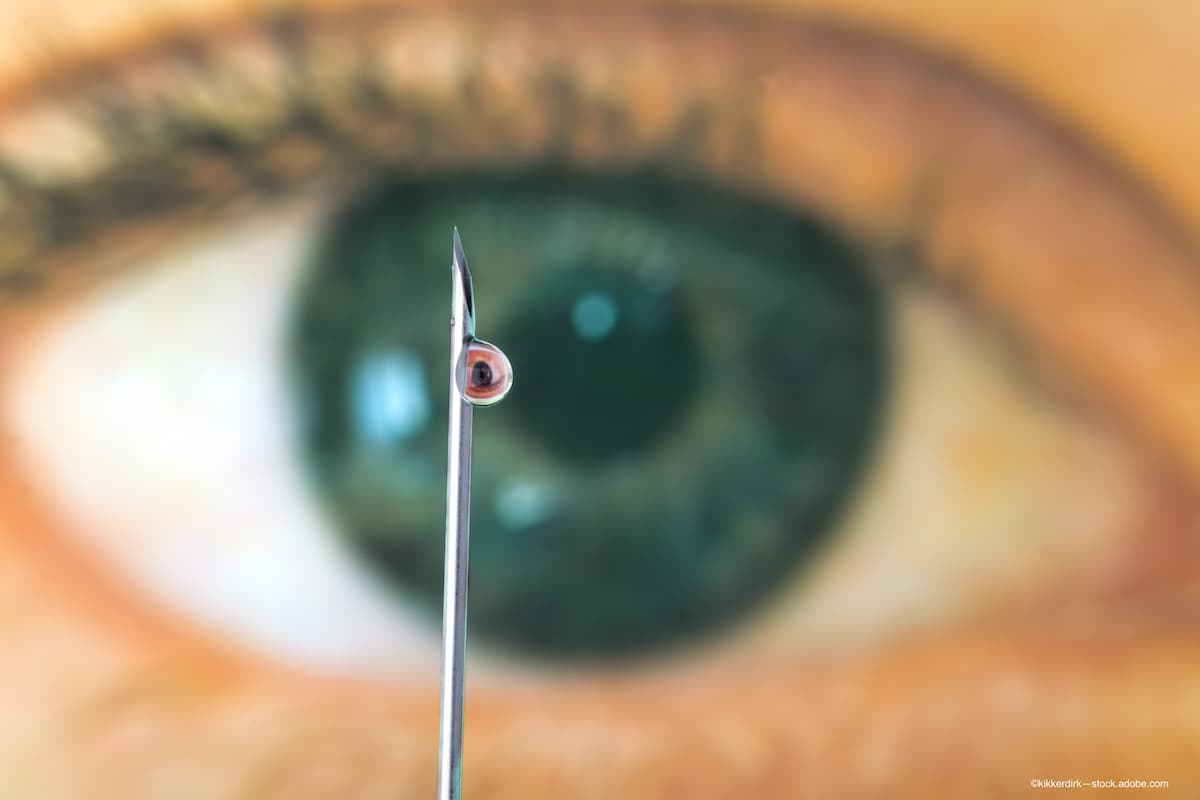

These are injected intravitreally monthly or every other month in patients with GA. In the phase 2 FILLY trial (NCT02503332), patients randomized to pegcetacoplan experienced a 20% to 29% reduction in growth rate of the GA lesions. Weng believes that this is an exciting result.

“We may finally have a treatment to offer these patients that can help them preserve their visual acuity for a longer period of time,” she said.

Wet AMD

In contrast to dry AMD, a number of effective treatments that are injected intravitreally are currently available for this form of the disease. The downside to this approach is that patients must undergo frequent injections for indefinite periods of time.

“This heavy treatment burden is not sustainable for many patients and contributes to suboptimal visual acuity outcomes,” Weng said.

Looking past intravitreal injections, patients will have access to a number of therapies on the horizon that will ease the treatment burden.

One of these is the recently FDA-approved port delivery system with ranibizumab (Genentech). This surgical implant is a reservoir that is implanted into the vitreous cavity that slowly releases concentrated forms of ranibizumab over longer periods of time.

Faricimab (Roche) is a recently approved bispecific antibody that targets two distinct pathways. One part of the molecule blocks vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A and the other part of the molecule blocks angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2), which is also involved in angiogenesis.

OTX-TKI (axitinib intravitreal implant, Ocular Therapeutix) is an intravitreal hydrogel containing a tyrosine kinase inhibitor; this product releases the drug in the eye over a period of 6 months or longer. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have a broader activity compared with anti-VEGF drugs, Weng explained.

At-home monitoring using optical coherence tomography (OCT), which is operated by patients, is an evolution in imaging that was recently introduced. This technology not only provides patient surveillance but also allows retinal changes associated with AMD to be recognized earlier than might happen through scheduled in-office examinations, thus facilitating earlier appropriate treatment. This may allow for more personalized treatment, she pointed out.

Gene therapy has been a huge step in many arenas in medicine and this is especially true in ophthalmology.

“This is science fiction turned into reality,” Weng said.

One gene therapy has been approved for use in ophthalmology for RPE65 deficiency–associated retinal dystrophy. Investigators are currently trying to determine if gene therapy can be applied to other more common diseases, such as AMD.

“We are leveraging the biofactory concept; that is, injecting a transgene into the eye and allowing the eye to then produce its own supply of anti-VEGF therapy,” Weng noted. “If that works, this could potentially be a one-and-done treatment that would significantly reduce or even eliminate the patient’s treatment burden.”

A few different routes of administration are being considered in gene therapy for AMD—not just intravitreal or suprachoroidal, but also via a subretinal route; this latter route would require a vitrectomy and a catheter with subretinal gene therapy that is injected into the subretinal space.

In addition to the dry and wet forms of AMD, diabetic diseases are other potential targets in ophthalmic gene therapy.

Christina Y. Weng, MD, MBA

E: Christina.Weng@bcm.edu

This article is adapted from Weng’s presentation at the virtual Real World Ophthalmology 2021 meeting. She is a consultant to Allergan/AbbVie, Alcon, Alimera Sciences, Novartis, Genentech, Regeneron, D.O.R.C., and REGENXBIO.

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.