Identifying new forms of infectious uveitis

Evidence suggests more ophthalmologists should perform aqueous sampling and viral testing in hypertensive anterior uveitis cases.

Reviewed by Soon-Phaik Chee, MD

Clinicians who simply treat hypertensive anterior uveitis with topical steroids to reduce inflammation may be putting their patients’ vision at risk. A growing body of evidence suggests that a significant portion of anterior uveitis associated with ocular hypertension is caused by viral infection. In most cases, failing to treat the infection can lead to treatment failure and impaired vision.

“Failure to diagnose the viral infection may lead to mismanagement with steroids alone, which may result in glaucoma and cataract formation” said Soon-Phaik Chee, MD, professor and senior consultant at the Singapore National Eye Centre. “In CMV (cytomegalovirus) infection, this may lead to corneal decompensation and the need for corneal transplant. Therapy is available for many of these viruses, but only when the cause of anterior uveitis is diagnosed correctly.”

Herpes family viruses, including herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Epstein-Barr virus are recognized as potential causes of uveitis. CMV, rubella, human herpes virus 6 and parechovirus are more recent entities, with the latter two being rare. Anecdotal reports suggest that few ophthalmologists routinely test patient with anterior uveitis and ocular hypertension for viral infection.

Blood sampling for serology is seldom conclusive, she continued, and confocal microscopy has diagnostic limitations. But most viral infections are readily detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing early in the course of infection.

All it takes is an anterior chamber tap using a fine needle. A sample of 0.1ml of aqueous humor is sufficient for both PCR and Goldmann-Witmer coefficient (GWC) analysis. Aqueous GWC is more sensitive than PCR for HSV, VZV, CMV and rubella virus while PCR is more sensitive for toxoplasmosis. Combining PCR and GWC improves the overall sensitivity of testing and diagnosis.

“CMV serology is positive in almost all of us as adults in Singapore,” Dr. Chee said. “Who would have thought that CMV would have caused this problem in the eyes of immunocompetent people? We know that CMV causes retinitis in immunocompromised and HIV patients, but very few ophthalmologists in the United States and many other countries would tap the anterior chamber for a specific diagnosis in an immunocompetent patient. Our findings suggest that they should.”

Related: Why infections related to PK require intense vigilance

A recent unpublished study of 221 patients and 229 eyes at the Singapore National Eye Centre treated between 2008 and 2012 found that fewer than half of patients with hypertensive anterior uveitis tested negative for viral infection. More than half, 51.5 percent, tested positive for CMV, 5.2 percent tested positive for HSV and nine percent tested positive for VZV. Similar testing in Germany found a significant number of patients with rubella virus infection in addition to other species.

Beyond clinical signs

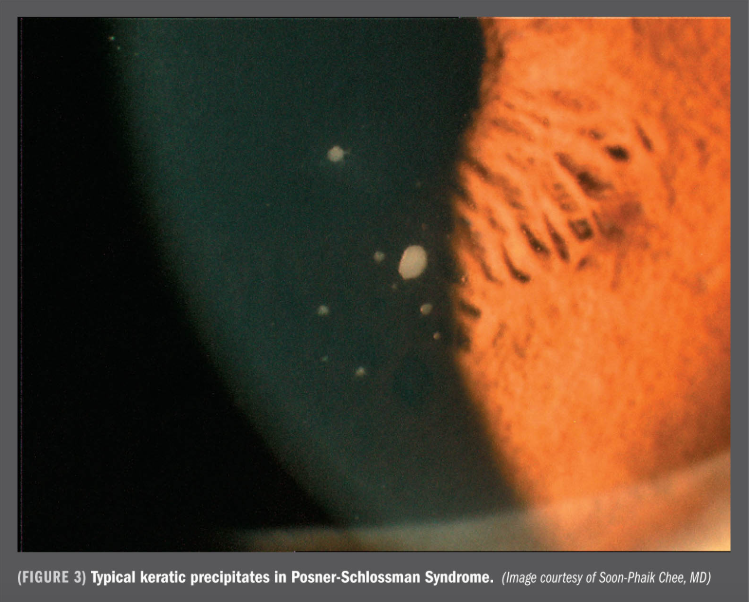

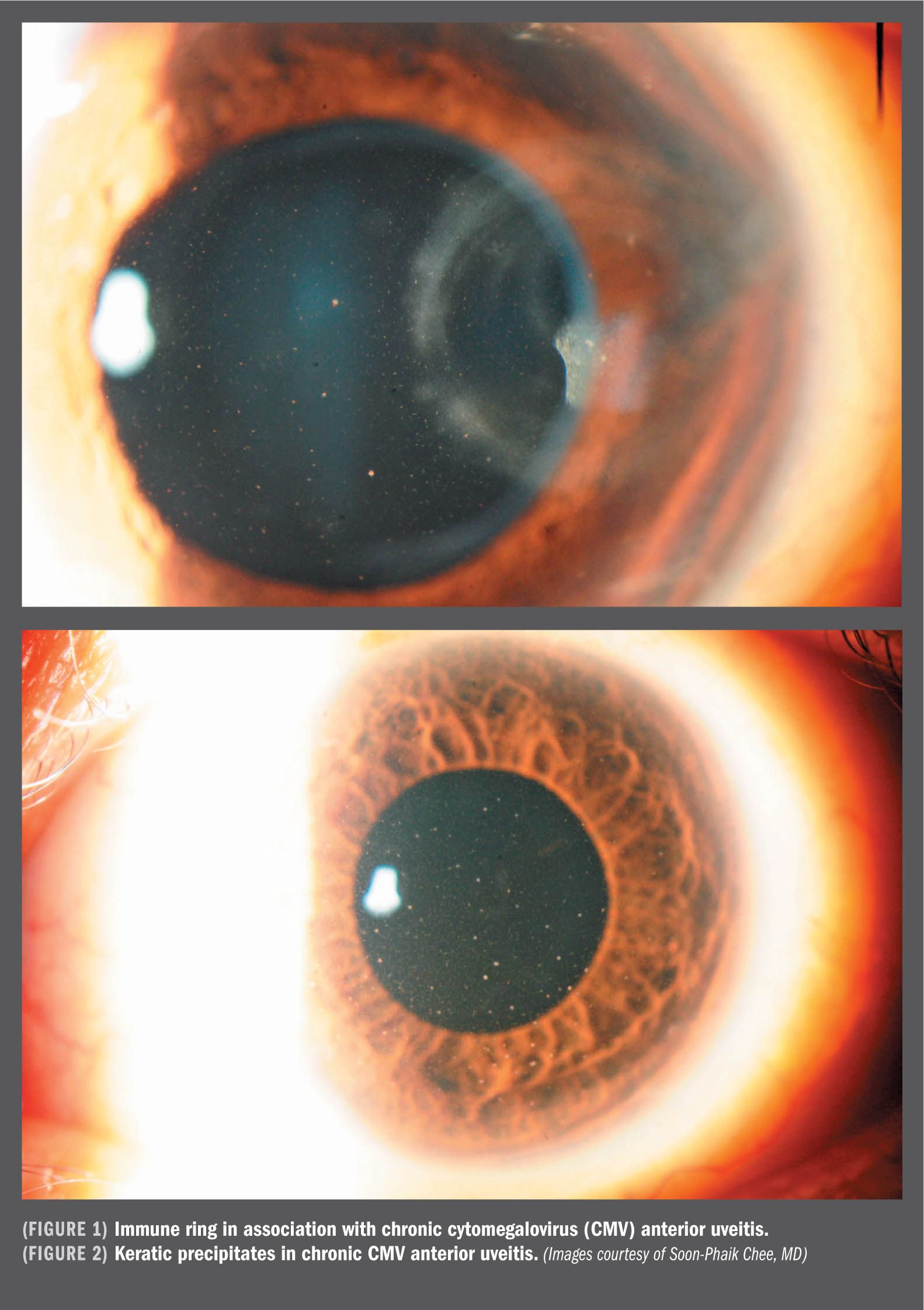

It can be difficult to identify viral infection from clinical signs alone, Dr. Chee said, and virtually impossible to identify the specific pathogen without an anterior chamber tap and testing. CMV, for example, can present in the anterior chamber as acute relapsing hypertensive anterior uveitis, also known as Posner-Schlossman syndrome (PSS), as Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI) or corneal endotheliitis as well as sector iris atrophy with iritis. Eyes with CMV-associated anterior uveitis do not show corneal scars, posterior synechiae, flare or fibrin and there is no clinically evident posterior segment involvement. Rubella and other viral infections can present with very similar features.

“The predominant types of viral infection varies from country to country, but reports in the literature suggest that herpes virus infection is common worldwide,” Dr. Chee said. “If the patient presents with ocular hypertension or has iris atrophy, they should be tested for viral infection to ensure appropriate treatment.”

For patients with rubella infection, ignore the infection and treat the cataract and glaucoma.

For patients with CMV infection, about two-thirds respond to ganciclovir gel 0.15 percent. Higher doses may be needed in patients who do not respond.

If topical therapy fails, she recommended oral valganciclovir 900 mg twice daily until PCR is negative, followed by 900 mg each morning. Expect to use oral valganciclovir for at least two to three months and the topical formulation for at least 6 months to reduce the risk of recurrence. Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories or corticosteroids are useful to treat inflammation.

A pilot study using ganciclovir 2% eye drops showed treatment to be as efficacious as ganciclovir 0.15% gel for the control of CMV anterior uveitis without significant ocular surface side effects.

“The evidence suggests that more ophthalmologists should be performing aqueous sampling and viral testing in order to obtain a specific diagnosis for patients with hypertensive anterior uveitis,” Dr. Chee said. “PCR is a relatively recent molecular diagnostic tool that can amplify small amounts of viral DNA that has become more widely available commercially. Not all clinicians are aware of this diagnostic tool, but obtaining a specific diagnosis and identification of the infectious agent is the only way to choose the appropriate therapy.”

Disclosures:

Soon-Phaik Chee, MD

E: chee.soon.phaik@snec.com.sg

This article was adapted from Dr. Chee’s presentation at the 2015 meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Dr. Chee did not indicate any financial interest in the subject matter.

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.