Inherited retinal disease: Gene therapy ushers new era

Ophthalmologist provides patient counseling pearls for selected retinal dystrophies

This article was reviewed by Christine Kay, MD.

The first retinal gene therapy, voretigene neparvovec-rzyl (Luxturna, Spark Therapeutics), was approved by the FDA in 2017. More than 3 years later, the field has a rapidly changing horizon, according to Christine Kay, MD.

“The standard of care for inherited retinal diseases has been elevated to a new level, requiring early diagnosis, genetic testing, and familiarity with clinical trials so that we can correctly counsel our patients,” said Kay, a retina specialist with Vitreo Retinal Associates in Gainesville, Florida, and an affiliate assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Florida in Tampa.

Kay provided an overview of gene therapy and discussed current gene therapy clinical trials and patient counseling pearls for selected inherited retinal diseases.

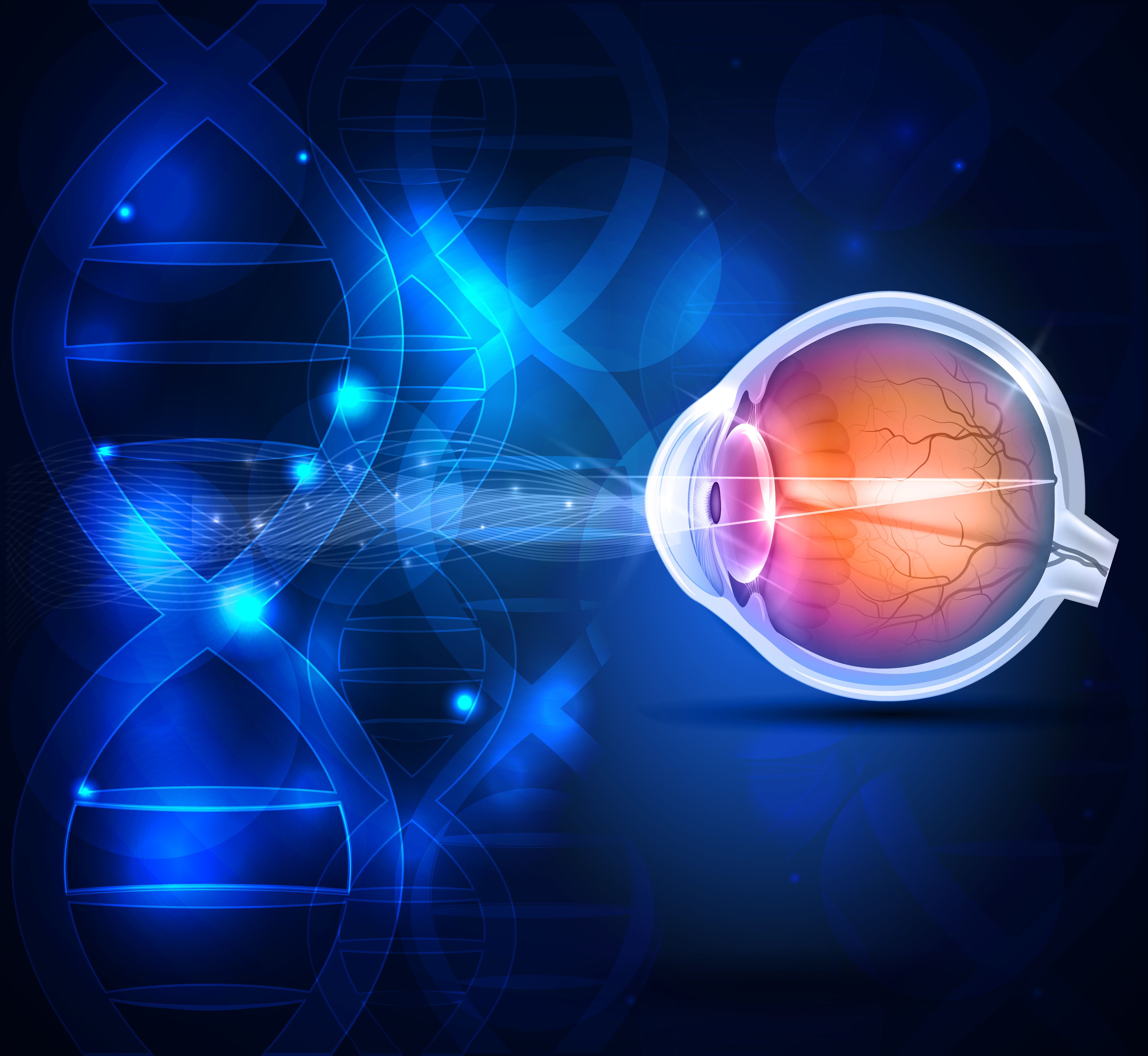

Gene therapy categories

Gene therapy for retinal dystrophies involves several different techniques that vary depending on the type of mutation. For recessive diseases in which the goal is to replace a missing function, the therapy is based on an augmentation (replacement) strategy. In contrast, for dominant diseases in which the mutation is causing protein misfolding or toxicity, gene therapy aims to suppress or inactivate the toxic gene. Strategies include using short synthetic single-stranded oligonucleotides that can alter RNA, and CRISPR gene editing to manipulate DNA in vivo, said Kay.

For multifactorial diseases such as age-related macular degeneration, for which there is no single underlying genetic cause, gene therapy can provide an additional means of introducing a therapeutic, such as an anti-VEGF agent. Non–genotype specific gene therapy using neuromodulation or optogenetics is an approach employed when the causative gene for a disease is not known. Its goal is to genetically alter ganglion cells to increase their photosensitivity.

Clinical care and clinical trials for retinal diseases

Multiple clinical trials of therapeutics for Stargardt disease are ongoing. These include a lentivirus gene therapy trial, a stem cell therapy trial, studies investigating orally administered drugs—one evaluating a chemically modified vitamin A and another examining a visual cycle modulator—and a study of an intravitreal complement inhibitor.

According to Kay, genetic testing is critical for patients with Stargardt disease and should be done to confirm mutations in the ABCA4 gene. In addition, physicians should advise patients to avoid supplemental vitamin A and protect their eyes in sunlight. Counseling should also include a discussion of “Fishman’s rule” that gives patients an idea of their disease’s natural history.

“Vision can decline slowly until acuity reaches 20/40, at which point there is typically a 7- to 10-year period of decline to reach the typical end stage of 20/200,” Kay said.

Current gene therapy trials for Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) include one involving antisense oligonucleotide therapy and another using a CRISPR system for gene editing. Kay noted that LCA is often misdiagnosed as retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

“Clinicians should ask about congenital onset and nystagmus and be aware of a possible association between LCA and the autism spectrum as well as misdiagnosis with these patients,” she said.

CNGB3-achromatopsia is another disease for which there are ongoing gene therapy trials. It can mimic blue cone monochromacy, Kay said, although patients with the latter typically have slightly better acuity and a better result on the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 Hue Color Vision test. It is possible to distinguish between the 2 conditions by using electroretinography or, more easily, genetic testing. To address the exquisite photosensitivity or photoaversion associated with achromatopsia, Kay recommended that patients wear red-tinted lenses.

Representing a progressive, later-onset, diffuse photoreceptor disease, RP is relatively common, with a prevalence of 1 in 4000 individuals. Kay said that patients with RP should have genetic testing to identify the underlying mutation that will determine their candidacy for ongoing clinical trials. In addition, physicians should monitor these patients for cystoid macular edema (CME) using optical coherence tomography.

“CME is common in patients with RP and should be treated with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors as first-line therapy as well as with steroidal and nonsteroidal therapy to preserve the foveal structure,” Kay said.

Regarding other retinal diseases, investigators are examining antisense oligonucleotide therapy for the treatment of Usher syndrome due to mutations in exon 13 of the USH2A gene. Choroideremia is also the subject of multiple ongoing gene therapy trials.

Further, the National Eye Institute is the sponsor of a gene therapy trial for gyrate atrophy. According to Kay, genetic testing is not necessarily needed for diagnosing this condition, which can be ruled in or out based on the serum ornithine level. A finding of elevated ornithine also informs a decision about vitamin B therapy, she said.

Christine Kay, MD

e: christinekay@gmail.com

This article is based on Kay’s presentation at the American Academy of Ophthalmology 2020 virtual annual meeting. Kay is a consultant and/or investigator for multiple companies developing retinal gene therapies. She holds equity in Atsena Therapeutics and receives honoraria from the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute as a member of the data safety monitor board for a choroideremia trial.

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.