Introducing 3-D OCT to live surgery

The advent of three-dimensional optical coherence tomography to live surgery may bring greater clarity to how ophthalmologists visualize structures and how they operate.

Take-home message: The advent of three-dimensional optical coherence tomography to live surgery may bring greater clarity to how ophthalmologists visualize structures and how they operate.

Reviewed by Pravin U. Dugel, MD

No doubt the commercialization of optical coherence tomography (OCT) has forever changed the clinical management of retinal disorders. Its introduction into the surgical realm may be a game changer in its own right, said Pravin U. Dugel, MD.

Modern microscopes limit the surgeon’s view, and “axial information must be inferred from instrument shadowing and other indirect cues.”1

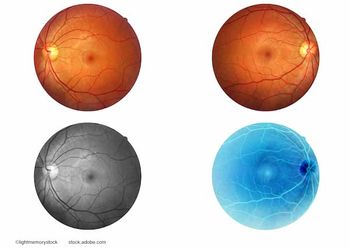

As advances in OCT technology have increased the ability of these devices to image ocular structures better, the category as a whole has moved into a wide variety of applications, including the ability to assess subretinal fluid, pigment epithelial detachments, and choroidal neovascular membranes.

Microscope-integrated OCT systems use spectral-domain OCT to “capture” live two-dimensional OCT images during surgery and provide viewing of three-dimensional (3-D) volumes on an external screen.

“There is a lot of misunderstanding around 3-D OCT technology,” said Dr. Dugel, managing partner, Retinal Consultants of Arizona, Phoenix, and clinical professor, University of Southern California Eye Institute, Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles. “It involves putting the image on an AV screen in a digital format and not looking through the microscope. There is a great deal of misconception as to why this is important.”

Though there are some ergonomic benefits, “those are really almost immaterial-they are very minor advantages,” said Dr. Dugel, who is also a member of the Ophthalmology Times Editorial Advisory Board.

The ‘game changer’

Introducing 3-D OCT to live surgery is going to change ophthalmology’s paradigm entirely in terms of how ophthalmologists visualize structures and how they operate, Dr. Dugel said.

“It’s all about the digitalization of the picture,” he said.

Dr. Dugel equated the digitalization to “building a better Polaroid camera or digitalizing your picture on a smartphone.”

Once the image is digitized, it can be made brighter, dimmer, or manipulated in imaging software programs.

“Building a better Polaroid-which would be analogous to a better microscope-is not going to allow you to do that. There's a limit that we’ve already reached and there’s not a whole bunch higher to go,” he said. “We've done proof-of-concept studies where we have looked at informatics from four different companies and have been able to incorporate informatics into our systems.”

The problem for surgeons is that the information is in the clinic (such as photos, OCTs, and fluorescein angiograms) and is discarded when the patient goes to the operating room. In short, the necessary information just does not travel from clinic to the operating room, he said.

“What we’ve done is to create a seamless flow of information from the clinic to the operating room as we need it, that is, on demand,” Dr. Dugel said. “That’s not an easy task.”

For the system to work correctly, there needs to be exact registration, “meaning the information has to overlap perfectly, which is hard enough,” he said. “In addition, you also have to have navigation, meaning that the picture and that overlaid information have to move perfectly in concert because the eye doesn’t stay still.”

Once the overlay of information that includes registration and navigation is paired with the various software and imaging modalities different companies offer, “that’s when it will really be useful,” Dr. Dugel said. He noted he is an investigator in a concept study that has incorporated photographs, angiograms, OCTs, and multispectral imaging to create a real-world, real-life 3-D image that can be used during surgery.

Dr. Dugel explained the concept of true 3-D imaging in real-time for surgery. Older aircraft, like DC-3s, have large windows in the cockpit because the pilots and engineers needed as wide a view as possible to determine weather and terrain details.

Modern airplanes, however, have small windows for the pilots because they now rely on monitors and navigation systems that allow them to manipulate what data they need-be it GPS, traffic patterns, or weather patterns-and receive the information in real-time.

Dr. Dugel said he anticipates being able to “click in and out to bring the information I need immediately up on screen.”

For instance, if he is peeling a membrane and wants to know its impact on photoreceptor cells, “I can click and get those informatics immediately,” Dr. Dugel said.

Or, if he is performing a laser procedure and needs to know oxygen intake levels or whether there is a lack of oxygenation in certain parts of the retina, the system will be able to show that.

“That’s where we’re headed with surgery because we’ve now been able to digitalize the image,” he said. “We can import informatics that are perfectly registered and navigated and are on demand. That is the holy grail.

“Informatics is what’s essential for all of us and to 3-D systems,” Dr. Dugel said, “and it’s what is going to make us better surgeons.”

Reference

1. Carrasco-Zevallos OM, Keller B, Viehland C, et al. Optical coherence tomography for retinal surgery: Perioperative analysis to real-time four-dimensional image-guided surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:OCT37–OCT50. DOI:10.1167/iovs.16-19277

Pravin U. Dugel, MD

This article was adapted from Dr. Dugel’s presentation at Dr. Dugel’s presentation at the 2016 congress of the European Society of Retina Specialists (EURETINA). Dr. Dugel has financial interest with Alcon Laboratories, Annidis, Novartis, OD/OS, and TrueVision.

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.