Real-world UK ranibizumab DMO outcomes match trials

Patients treated with ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech) for diabetic macular oedema (DMO) in the National Health Service of the United Kingdom can fare about as well as patients in clinical trials, a review of patient records suggests.

Patients treated with ranibizumab (Lucentis, Genentech) for diabetic macular oedema (DMO) in the National Health Service of the United Kingdom can fare about as well as patients in clinical trials, a review of patient records suggests.

“This Moorfields study on a cohort of 200 eyes shows that results from landmark clinical trials are reproducible in clinical practice to a large extent,” wrote Namritha Patrao and colleagues at Moorfields Eye Hospital and University College of London, United Kingdom.

They published the finding in

In large randomized clinical trials, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatments including ranibizumab have achieved much more success than any previous therapy. In these trials, about half of patients gained 2 lines of best-corrected visual ETDRS visual acuity, and almost a third gained 3 lines.

The European Medicines Agency licensed ranibizumab in 2011 based on some of these trials.

However, clinical practice presents challenges not always present in trials. A multiethnic population with varying levels of diabetic control, multiple comorbidities, and difficulty attending appointments complicates care.

Patrao and colleagues wanted to know whether patients treated in National Health Service clinics would enjoy the same benefits from treatment as patients in trials.

They looked at records on 200 eyes in 164 patients treated at the Moorfields Eye Hospital. Of these patients, 21.95% had bilateral injections. Their mean baseline visual acuity was 54.4 letters and mean central subfield thickness was 490.16 µm.

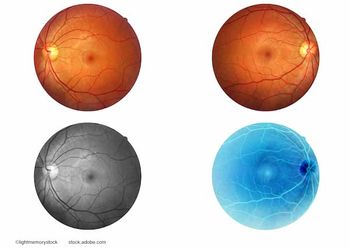

The eyes received 3 monthly injections of 0.5 mg ranibizumab, then further injections at the clinician’s discretion aimed at achieving stability based on twice monthly tests of visual acuity and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Laser therapy and panretinal photocoagulation were administered at the clinician’s discretion.

The researchers were able to follow 195 eyes for 12 months, of which 4 had missing visual acuity records.

The remainder gained a mean of 6.6 letters, with 40.3% gaining at least 10 letters, 8.9% losing at least 10 letters, and 6.3% losing at least 15 letters.

Among those treated in both eyes, the eye treated first had a mean visual acuity gain 7.42 letters and the eye treated second had a mean gain of 9.33 letters.

Those who started with 60 letters or fewer gained a mean of 8.8 letters, while those with a baseline between 61 and 73 letters lost a mean of 4.3 letters.

The proportion of those with visual acuity of at least 73 letters tripled from 9.5% to 29.3%, and the proportion of eyes with fewer than 39 letters dropped from 15% to 10.5%.

Eyes that had received macular laser therapy before ranibizumab gained a mean of 7.5 letters, while those being treated for the first time had a mean of 4.8 letters.

Out of 23 eyes that received macular laser therapy during the study period and had data available, the mean change in visual acuity was +11.6, compared with +5.9 in those that did not receive macular laser therapy.

Central subfield thickness was reduced by a mean of 133.9 µm over the year of follow-up, while mean macular volume decreased by 1.5 mm3. At the end of the year, 42.5% of eyes had a central subfield thickness of more than 350 µm.

The patients received a mean of 7.2 injections during the year, which was similar to the 6.8-7.0 injections patients received in the RESTORE trial, but less than the 8-9 injections in the Protocol I study.

Results of the Moorfields study were similar to those on a similar “real world” study in Demark, where 62 eyes received an average of 5 injections over 9-15 months, gained a mean of 5 letters, and lost a mean of 98 µm in central subfield thickness.

The researchers attributed the slightly lower visual acuity gain in their study compared to the landmark clinical trials to the broad range of patients, some of whom might not have been included in the trials and many of whom might have poor diabetic control or difficulty getting to appointments.

They noted that patients in this study had fewer injections on average than in Protocol I with its “very robust treatment algorithm.”

They cited some limitations of the study. First, unrefracted visual acuity recordings and nonreferenced OCT images were performed in non-trial settings at successive visits. Second, 25 clinicians were involved and might have employed varying criteria for retreatment.

“Although all clinicians would treat a >10 letter drop in visual acuity or a >50 mm increase in central subfield thickness on OCT, patients may have been treated on occasion if a >5 letter drop in visual acuity or a significant change in intraretinal fluid was noted, in the opinion of the clinician,” they wrote.

Still, they concluded, the study provides evidence that patients with DMO can benefit from ranibizumab injections on a three-month loading schedule, followed by further injections as needed.

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.