Research reveals genetic signatures of AMD, may lead to improved diagnosis

The discovery of molecular signatures of age-related macular degeneration will help with better diagnosis and treatment of this progressive eye disease.

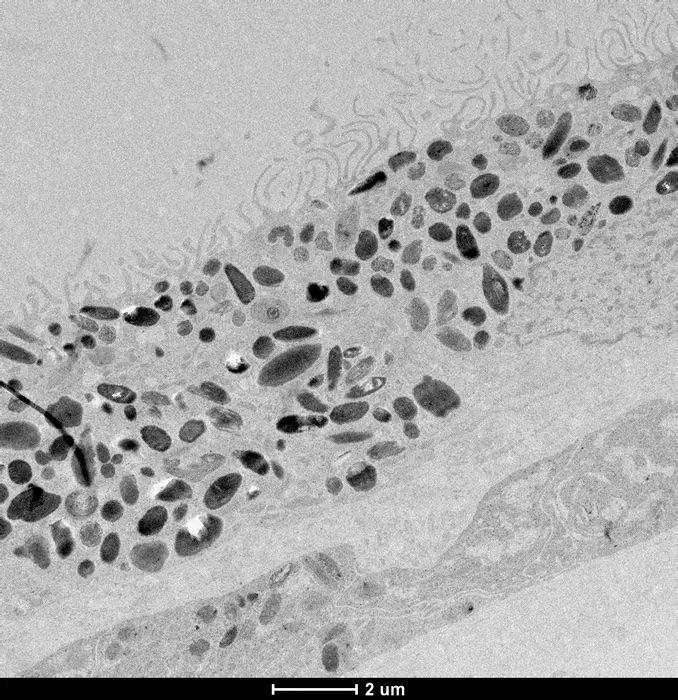

Black and white electron microscopy imaging of retinal pigment epithelium cells. (Image courtesy of Grace Lidgerwood, MD)

Better diagnosis and treatment of age-related macular degeneration is a step closer, thanks to the discovery of new genetic signatures of the disease.

Scientists from the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, the University of Melbourne, the Menzies Institute for Medical Research at the University of Tasmania and the Center for Eye Research Australia, reprogrammed stem cells to create models of diseased eye cells, and then analyzed DNA, RNA and proteins to pinpoint the genetic clues.

According to Joseph Powell, PhD, joint lead author and Pillar Director of Cellular Science at Garvan, researchers have tested the way that differences in people’s genes impact the cells involved in age-related macular degeneration.

“At the smallest scale we’ve narrowed down specific types of cells to pinpoint the genetic markers of this disease,” Powell said in a statement. “This is the basis of precision medicine, where we can then look at what therapeutics might be most effective for a person’s genetic profile of disease.”

Age-related macular degeneration, or AMD is the progressive deterioration of the macular—a region in the centre of the retina and towards the back of the eye—leading to possible impairment or loss of central vision. Around one in seven Australians over the age of 50 is affected, and about 15 per cent of those aged over 80 have vision loss or blindness.

The underlying causes of the deterioration remain elusive, but genetic and environmental factors contribute. Risk factors include age, family history and smoking.

The research is published in the journal Nature Communications.

According to a news release from Garvan, the researchers took skin samples from 79 participants with and without the late stage of AMD, called geographic atrophy. Their skin cells were reprogrammed to revert to stem cells called induced pluripotent stem cells, and then guided with molecular signals to become retinal pigment epithelium cells, which are the cells affected in AMD.

Retinal pigment epithelium cells line the back of the retina and are essential to the health and functioning of the retina. Their degeneration is associated with the death of photoreceptors, which are light-sensing neurons in the retina that transmit visual signals to the brain and are responsible for the loss of vision in AMD.

Analysis of 127,600 cells revealed 439 molecular signatures associated with AMD, with 43 of those being potential new gene variants. Key pathways that were identified were subsequently tested within the cells and revealed differences in the energy-making mitochondria between healthy and AMD cells, rendering mitochondrial proteins as potential targets to prevent or alter the course of AMD.

Further, the molecular signatures can now be used for screening of treatments using patient-specific cells in a dish.

“Ultimately, we are interested in matching the genetic profile of a patient to the best drug for that patient. We need to test how they work in cells relevant to the disease,” co-lead of the study Alice Pébay, PhD, from the University of Melbourne.

Powell and co-lead authors Pébay, and Alex Hewitt, PhD, from the Menzies Institute for Medical Research in Tasmania and the Centre for Eye Research Australia, have a long-running collaboration to investigate the underlying genetic causes of complex human diseases.

“We have been building a program of research where we're interested in stem cell studies to model disease at very large scale to do screening for future clinical trials,” Hewitt said in the releaese.

In another recent study, the researchers uncovered genetic signatures of glaucoma—a degenerative eye disease causing blindness—using stem cell models of the retina and optic nerve.

The researchers are also turning their attention to the genetic causes of Parkinson’s and cardiovascular diseases.