SOE 2023: Optic Neuropathy Versus Maculopathy

Video transcript

Editor’s note: This transcript has been edited for clarity.

David Hutton: I'm David Hutton of Ophthalmology Times. We're covering the European Society of Ophthalmology Congress being held in Prague. I'm joined today by Dr. Nicholas Volpe, who will make a presentation titled "Optic Neuropathy Versus Maculopathy." Thank you so much for joining us today. Dr. Volpe, tell us about your presentation.

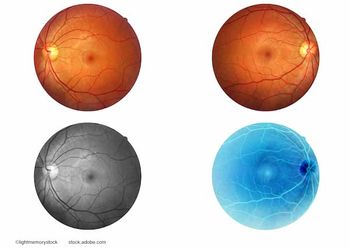

Nicholas Volpe, MD: Thanks very much, David and Ophthalmology Times for inviting me to present this little summary video of my talk on maculopathy versus optic neuropathy. This has for ages been a very hot topic for ophthalmologists, because there are a group of patients that have unexplained vision loss and relatively normal appearing fundi, that is both the macula and the optic nerve. At first glance appears to be healthy. And for decades, we would go back and forth – is this an optic nerve problem? Is it a macular problem. And I would say that, of course, the whole game has been revolutionized by the advent of OCT. Which has really given us a much finer anatomic view of what's happening in the retina.

So many of the conditions that we used to kind of go back and forth on is – this a cone dystrophy or is it an optic nerve problem? Well, the cone dystrophy has an abnormal OCT that we would not have been able to see with traditional ophthalmoscopy, and it makes it a little bit easier to make that distinction. That being said, even today, with all the modern imaging that I have access to, there are still patients in which we have various symptoms of unexplained vision loss. Sometimes it's blind spots, or visual field defects. Other times it might be flashing lights or photopsia. And we're going back and forth to try to decide, is this an optic nerve or retina problem? Or is it both?

Remember, there are lots of things that happen to people, for instance, neuroretinitis or syphilis, for example, that can affect both. And localizing the disease and where the symptoms are coming is not necessarily easy, but in that case, generally there's a specific treatment to follow regardless of how it localizes. So we'll talk about a little bit of the history and the things that favor retina problems versus optic nerve problems. For instance, something like pain or any symptoms of discomfort, for sure favor optic nerve problems. The loss of color vision might be the same in both. The types of scotomas are very different, patients with retina problems generally have very small scotomas. And the presence of flashing lights and other positive visual phenomena generally really favor retinal diagnosis. But as we'll explain, once you approach the patient in a logical fashion, and include imaging, as well as carefully done visual fields. And occasionally, electrophysiology, specifically, either electroretinograms or electroretinograms that are multifocal, specifically looking at areas of the macula.

Between those types of testing, we're very, very rarely unsure of is the ganglion cell layer loss, an optic nerve problem? Is the ellipsoid level disrupted, and therefore localizing to an outer retina problem? Can we identify something like acute macular retinopathy, which is sometimes very hard to see, on ophthalmoscopy, presents with a sudden onset of a scotoma. And there you go, very easy diagnosis to make with good optical coherence tomography. So, in the end, what we're going to talk about is a very systematic approach, characterizing the history in the details, really being very specific about is it a blind spot, a visual field defect, does it have positive qualities, and then going very quickly to our advanced imaging techniques, particularly in addition to fluorescent angiography, occasionally, OCT, and occasionally electroretinograhy and in that setting, it's not difficult to distinguish those 2 entities in most patients.

There is one other topic that I think is important for ophthalmologist to be aware of, and that both in the differential diagnosis of maculopathy versus optic neuropathy, are going to be patients with nonorganic or functional vision loss, where they have an unexplained symptom ophthalmoscopy looks normal. But if you take it to the next level can't explain the symptom and ganglion cells normal, ellipsoids normal, ERG is normal. Then we have really hard structural evidence that there isn't really anything wrong with the eye itself and the visual apparatus, and that can often be non-organic or functional vision loss, with the one exception as that there will be a patient that creeps into this differential diagnosis that has vision loss that is on an occipital or brain basis, where there are symptoms that accompany perfectly healthy eye exam, but blind spots, hemianopic scotoma, positive visual phenomena that are manifestations of eye disease.

So if all of this testing leads you to normal results in terms of the appearance of the optic nerve, the OCT the ganglion cell layer, the ellipsoid level. Then you're going to have to revisit and say is it functional vision loss, or might it be brain based vision loss and have to pursue that with neuro imaging such as an MRI scan. So in the modern era, the entities are generally easy to distinguish, they're critically important to distinguish because of the kinds of conditions that might work their way into the differential diagnosis of either, for example, something like a toxic optic neuropathy or an acute inflammatory optic neuropathy versus an acute macular neuroretinopathy or enlarged blind spot syndrome. And again, the differential diagnosis will broaden to unexplained vision loss that would need to include functional and cortically based vision loss in some patients. So thank you for asking me for my comments. I think we we're really armed with great tools as ophthalmologists now to distinguish these patients. Generally with careful history, taking careful examination, characterization of deficits and imaging, we can get our patients to a point where we're really confident of the diagnosis

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.