Successful ocular surgery in patients with chronic uveitis

While operating on a patient with chronic uveitis presents some challenges, there are a few pearls that may increase success.

Surgery in a patient with uveitis presents a number of challenges. First, the visual outcomes of surgery are likely to be worse than in patients without uveitis. The procedure may also be more prone to uveitis-related surgical complications, such as damage to the cornea, iris atrophy or posterior synechiae, cystoid macular edema (CME), and epiretinal membranes.

Finally, there is also a risk of uveitis recurrence after surgery, even in a patient whose disease had previously been well controlled. The risks of surgery vary greatly, depending on the type and severity of uveitis, the type of surgery required, and the patient’s general health and comorbid conditions.

Related: Why uveitis is a leading and underestimated cause of visual morbidity in patients

In this article, I will primarily discuss cataract surgery, as it is the surgical procedure most frequently performed in patients with uveitis, and the one on which protocols for other types of surgery are based.

The first principle of surgery in patients with uveitis is that their uveitis should be completely and consistently controlled for at least three months prior to surgery. This objective is typically easier to achieve prior to an elective procedure like cataract surgery than an emergency repair of a retinal detachment. However, if the situation is urgent in some types of lens-induced uveitis, the surgeon may not have the luxury of waiting for complete and consistent control.

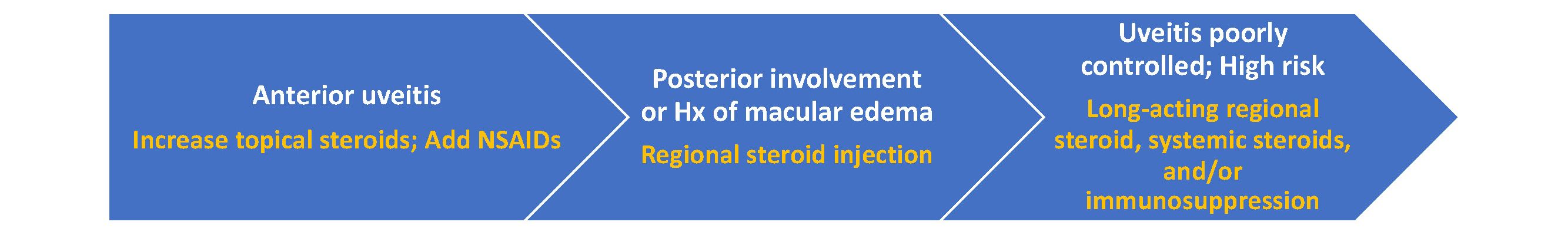

Strategies for controlling inflammation become increasingly aggressive with more severe uveitis. Certain uveitic conditions, including Fuchs uveitis syndrome, do very well with cataract surgery and may not even need extra perioperative steroids. A patient with a history of recurrent acute anterior uveitis that is well controlled with topical steroids, with no recent flareups, may also fare quite well.

In these patients, I typically increase the dose of topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1% every two hours) starting a couple days before surgery and continuing for a month after surgery, tapering back to baseline based on postoperative inflammation.

The risk of CME can peak 3 to 4 weeks after surgery, so it is important not to stop the steroids too soon. I also add a topical NSAID such as bromfenac or ketorolac, provided there is no medical contraindication. NSAIDs significantly reduce the risk of pseudophakic CME1 and should always be on board in patients with uveitis, even if the surgeon doesn’t use them in routine cataract cases.

Related: Treating chronic uveitis with fluocinolone acetonide implants

In those with any posterior involvement, including significant posterior synechiae, recent sarcoid panuveitis or Behçet’s disease, or any history of macular edema, much more aggressive measures may be needed. These patients may require regional steroid injections, systemic steroids, and/or systemic immunosuppression—essentially, whatever it takes to control the uveitis before surgery.

Although I may give patients a sub-Tenon’s triamcinolone acetonide injection or intravenous steroids at the time of surgery, I generally prefer to also have steroids on board before the day of surgery

For control of uveitis perioperatively, an intravitreal injection of the dexamethasone intravitreal implant 0.7 mg, (Ozurdex, Allergan) or preservative-free triamcinolone acetonide 2-4 mg 2 to 4 weeks prior to surgery is indicated. Remember that intravitreal triamcinolone is opaque and may blur the retinal reflex if it is still in the eye at the time of surgery. If the patient does have an intraocular pressure (IOP) response to the steroid, it typically lasts no more than 2 to 4 months and may be controlled with glaucoma drops.

A longer-lasting implant such as injectable fluocinolone acetonide 0.18 mg (Yutiq, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals) or fluocinolone acetonide 0.59 mg scleral-fixated implant, (Retisert, Bausch + Lomb), may be beneficial in a patient who has had local injections in the past and is not a steroid responder. Retisert requires surgical implantation, whereas Yutiq is administered via an in-office injection through a 25-gauge siliconized needle.

With the longer-duration implants, the patient may have adequate steroid coverage to not only control postoperative CME but to prevent recurrences of uveitis and macular edema for several years after surgery. We also have to consider the dose and location of these steroids. Yutiq contains about one-third the dose of fluocinolone acetonide that Retisert does (0.18 mg vs 0.59 mg), and because it sits more posteriorly in the eye, further from the ciliary body, may have a lower risk of inducing glaucoma.2,3

Related: Confirming uveitis treatment efficacy in study

Studies suggest that long-lasting intravitreal steroids can be as effective as immunosuppressive therapy in controlling uveitis and macular edema,4 so these are a great option for patients who can’t take oral steroids because of diabetes or high blood pressure, who are medically unable to take immunosuppressive therapy, or who would prefer to avoid these drugs.

Systemic immunosuppressants and local steroids can work very well in combination. For example, if the patient is already well controlled on a single immunosuppressant, I don’t usually add another immunosuppressant just for cataract surgery. Rather, I will use steroids in some form as adjunctive therapy.

Cataract surgery challenges

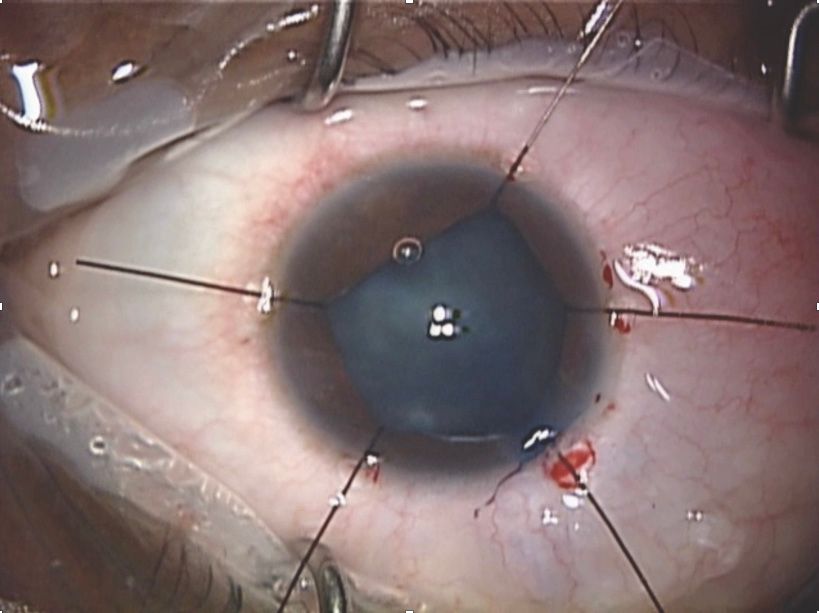

Being prepared to manage a small pupil is essential when performing cataract surgery in patients with uveitis, as these patients often have synechiae or iris atrophy. In some cases, manual iris stretching techniques may be sufficient, but iris hooks or pupil expansion rings are often required. Iris hooks take more time to place and may cause damage to the iris if placed incorrectly, but they provide a great deal of flexibility.

If I run into an intraoperative complication such as zonular dehiscence or a nuclear fragment that is floating peripherally and is difficult to visualize, iris hooks allow me to expand the pupil more in that particular meridian.

A Malyugin ring, by contrast, provides a fixed pupil size and is a larger piece of hardware that can complicate other aspects of the surgery. However, it is fast and easy to place and a large study suggested that the Malyugin ring and iris hooks are comparably effective.5

Related: International coalition categorizes 25 subtypes of uveitis using machine learning

In retinal surgery, performing scleral depression and getting a really good view of the peripheral retina will likely be easier with hooks than with a ring. Anyone who performs surgery in uveitic eyes should be comfortable with both types of devices.

A femtosecond laser can make cataract surgery easier in uveitic eyes with poor zonular support. However, a FLACS procedure also requires a longer duration of pupil dilation, which can be quite challenging in these eyes. Even with good dilation, it may be more difficult to achieve the laser capsulotomy, as blood from stretching the pupil may affect the focusing ability of the laser. For all these reasons, I typically opt for manual capsulorrhexis and phaco in my patients with uveitis.

Postoperatively, these patients may need aggressive cycloplegic therapy to prevent recurrent posterior synechiae. If synechiae do occur, I prefer to intervene quickly to avoid pupillary glaucoma. Unlike many routine cataract surgeries, the postoperative care for patients with uveitis should not be delegated to other clinicians. It is important to monitor carefully for any signs of inflammation or increased IOP, and to be sure to check both eyes in patients with bilateral uveitis, rather than just the operative eye.

Managing expectations

The outcomes of cataract surgery with a lens implant in several types of uveitis, including juvenile rheumatoid arthritis-associated uveitis, Behcet’s disease panuveitis, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, can be very disappointing. In some cases, the surgery seems to go well, but the vision just doesn’t improve as much as expected.

This may be due to an unrecognized retinal complication, such as an epiretinal membrane or a tractional detachment that couldn’t be seen on preoperative imaging through a dense cataract, but in some cases, there is no clear explanation for the poor result. Those with comorbid conditions (e.g., cataract + glaucoma + uveitis) may require multiple, staged procedures to achieve a satisfactory final visual result.

Related: Measuring intraocular inflammation with standard care imaging

For all these reasons, good patient education is absolutely critical to avoid postoperative dissatisfaction. Patients with uveitis often develop early cataract and may therefore be younger, of working age, and may still have residual accommodation that will be lost after surgery. They have a higher risk of complications and a longer recovery period than non-uveitis cataract patients, so it is important to under-promise (and hopefully, over-deliver).

Patients need to know that they probably won’t see 20/20 in the waiting room like their uncle Fred did after his cataract surgery last year. That said, I personally find it more satisfying to give a person with hand-motion vision a 20/40 visual outcome than to improve a routine 20/25 cataract patient to 20/20. With carefully individualized care, we can optimize the chance of good outcomes for our patients with uveitis.

James P. Dunn, MD

E: jpdunn@willseye.org

Dr. Dunn is a retina and uveitis specialist at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, PA, and has a particular interest in cataract surgery in patients with uveitis. He has no financial disclosures to report.

References

1. Wielders LHP, Lamermont VA, Schouten JSAG, et al. Prevention of cystoid macular edema after cataract surgery in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;160(5):968-998.

2. Jaffe GJ, Pavesio CE, Study investigators. Effect of a fluocinolone acetonide insert on recurrence rates in noninfectious intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis: Three-year results. Ophthalmology. 2020;127(10):1395-1404.

3. Eyepoint Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Full Prescribing Information. Yutiq.com. https://eyepointpharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/YUTIQ-USPI-20181120.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2021.

4. Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial Research Group; Kempen JH, Altaweel MM, Drye LT, et al. Benefits of systemic anti-inflammatory therapy versus fluocinolone acetonide intraocular implant for intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis: 54-month results of the Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial and follow-up study. Ophthalmology 2015;122(10):1967-75.

5. Balal S, Jbari AS, Nitiapapand R, et al. Management and outcomes of the small pupil in cataract surgery: Iris hooks, Malyugin ring or phenylephrine? Eye (Lond) 2020 Nov 12. Online ahead of print.

Related Content: Uveitis | Retinal Surgery | Ophthalmology | Retina in 2020 and Beyond

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.