- Modern Retina Winter 2023

- Volume 3

- Issue 4

Editorial: Cancer and the eye: Mysteries remain

As ophthalmology continues to advance, there is still room for more ocular cancer understanding and research.

Ophthalmology has a track record of being at the forefront when it comes to innovation and improving outcomes for patients. We have led the way in medicine in developments such as microsurgery, gene therapy, and the transition to ambulatory care, as opposed to hospital-based care.

But to my way of thinking, we still have work to do in the field of oncology. The treatment of babies with retinoblastoma today is light years ahead of where it was when I trained, but the management of uveal melanoma, the most common primary intraocular malignancy, has, shockingly, remained depressingly static. A recent review in Communications Medicine1 says it all:

- “No substantial survival differences have been observed between commonly used treatment modalities, patient sex and age, or calendar period between the last several decades.”

- “Currently available treatment options for primary tumors have limited effect on patient survival.”

- “There are no clinically available treatments with meaningful impact on survival in metastatic disease.”

So, while there has been dramatic progress in the treatment of many malignancies in recent decades, the treatment of uveal melanoma remains a glaring exception to the aforementioned tendency of ophthalmology to lead the way with innovative solutions.

To be fair, I might point out that the eye represents some unique obstacles, including the blood-ocular barrier,

immune privilege, and the relatively small number of these tumors that occur annually (about 7000 worldwide). By comparison, the therapies for glioblastoma multiforme are not particularly effective either.

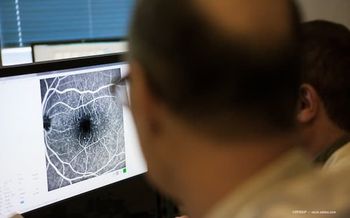

Reflecting the special relationship between the eye and cancer are the paraneoplastic syndromes in which fascinating ocular disorders result from the presence of neoplasias elsewhere in the body. One such rare condition and a proposed therapy are highlighted in this issue’s cover story. My hope is that this generation of ophthalmologists will put the pieces of the ocular oncology puzzle together, and ophthalmology will soon go from laggard to leader when it comes to this subspecialty.

Reference

Stålhammar G, Herrspiegel C. Long-term relative survival in uveal melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Commun Med.2022;2:18. doi:10.1038/s43856-022-00082-y

Articles in this issue

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.