Look for clues to simplify anterior uveitis diagnosis

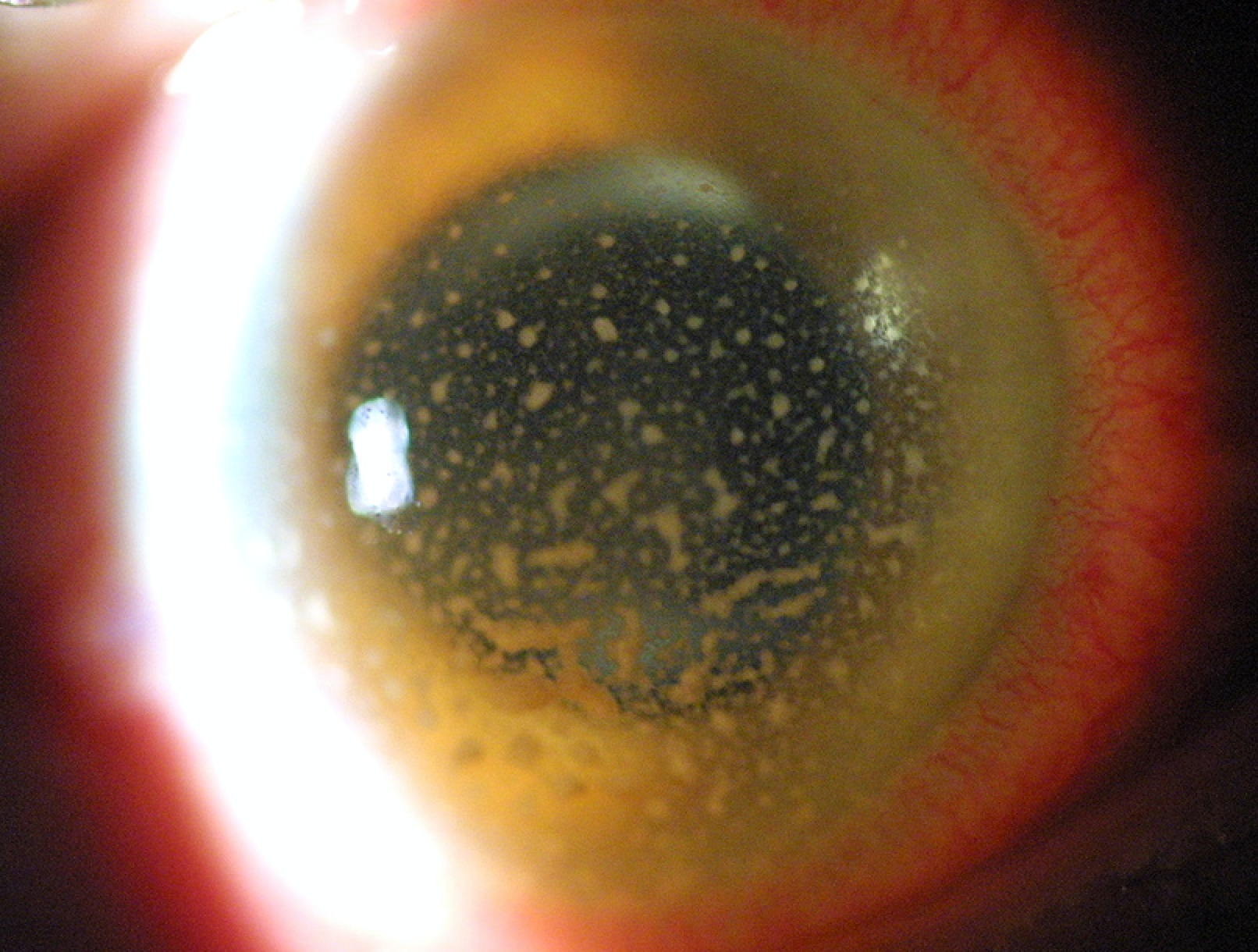

Granulomatous keratic precipitates in an eye with VZV iritis. (Image courtesy of Todd P. Margolis, MD, PhD)

Though anterior uveitis is associated with myriad conditions, a relatively short list of disorders accounts for the vast majority of cases.

Knowing the most common etiologies will help non-uveitis specialists make the diagnosis and initiate appropriate therapy or determine which patients are in the smaller subset who may need to be referred, said Todd P. Margolis, MD, PhD.

“One of the primary goals of the diagnostic evaluation for patients with anterior uveitis is to separate infectious from inflammatory etiologies because infectious anterior uveitis is treated with specific antimicrobial therapy whereas immunosuppression is indicated for inflammatory disease,” said Dr. Margolis, Alana A and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor and Chair, John F Hardesty MD Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO.

“Knowing the most common conditions associated with anterior uveitis helps to pinpoint the diagnosis, and by doing a Bayesian analysis, clinicians can avoid unnecessary testing that may be more likely to give a false positive result,” Dr. Margolis said.

RELATED: Get the ABCs of DSO

Age as a factor

Outlining the differential diagnosis of anterior uveitis, Dr. Margolis said that it is different in adults than in children.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is by far the most common cause of anterior uveitis in the pediatric population followed by idiopathic disease. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis (TINU) ranks third, and all other diagnoses are rare.

“TINU is likely to become more prevalent simply because it is now being recognized more,” Dr. Margolis said. “It is something to think about in a pediatric patient with chronic bilateral uveitis who does not have JIA.”

Idiopathic disease heads the diagnosis list for adult cases of anterior uveitis followed in descending frequency by HLA B27-related disease, herpetic disease (herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus [HSV and VZV]), and trauma. All other diagnoses comprise only a small percentage of cases of anterior uveitis in adults.

RELATED: Adalimumab efficacious for uveitis regardless of disease durationDiagnostic clues

Even before the slit-lamp examination, certain findings are helpful for developing the differential diagnosis. Features to note include whether the uveitis is episodic or chronic and whether it is unilateral, bilateral, or bilateral but present in one eye at a time.

Presence of a distinct skin rash suggests syphilis, and heterochromia indicates iris atrophy such as that seen in VZV or Fuch’s heterochromic cyclitis. Band keratopathy in a child is consistent with JIA and should raise suspicion of VZV in adults, although it can also be a feature of any chronic uveitis.

The differential diagnosis for a patient with anterior uveitis and scleritis includes VZV, HSV, tuberculosis, polyarteritis nodosa, relapsing polychondritis, or granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Lacrimal gland enlargement or conjunctival granuloma are signs of sarcoidosis. Acutely elevated IOP suggests infectious etiology, and loss of corneal sensation points to a herpetic cause, said Dr. Margolis, adding that he tests corneal sensitivity using dental floss rather than a cotton-tipped swab.

Slit-lamp findings that are helpful for establishing the diagnosis include hypopyon, keratic precipitates (KP) above the midline, iris atrophy and nodules, and corneal disease.

RELATED: Biologics may offer systemic therapy option for uveitis

Dr. Margolis explained that hypopyon is seen in anterior uveitis that develops after surgery or when the cause is infectious, Behçet disease, herpetic, or HLA B27-related. KP above the midline also points to infection with possible pathogens including HSV, VZV, and cytomegalovirus (CMV).

“Toxoplasmosis, which will involve the posterior segment, also presents with KP above the midline,” Dr. Margolis said.

Diagnoses to consider when there is corneal involvement include HSV and VZV. In particular, stromal disease, loss of corneal sensation, and endotheliitis. Chronic pseudodendrites point to VZV.

Associations with granulomatous KP and iris nodules include infection, Behçet disease, sarcoidosis, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, whereas iris atrophy primarily occurs with herpetic infection or rubella.

“Iris atrophy may also be seen when anterior uveitis is associated with the Uveitis-Glaucoma-Hyphema (UGH) syndrome, but then the diagnosis is usually obvious based on a poorly placed IOL,” Dr. Margolis said.

Pigmented cells in the anterior chamber suggest the presence of iris atrophy or its resolution, and may also be a sign of chronic disease. Otherwise, presence of anterior chamber cells is largely used to grade disease severity and response to therapy.

RELATED: Managing uveitic macular edema

Disclosures:

Todd P. Margolis, MD, PhD

E: margolist@wustl.edu

This article was adapted from Dr. Margolis’ presentation during Uveitis Subspecialty Day at the 2018 meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology. He has no relevant financial interests to disclose.

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.