Persistence is key when promoting surgical innovations

A surgical innovation is defined as a quantum improvement in the treatment of a particular disease or group of diseases, and it usually is developed by an individual or a small group working together, said John Thompson, MD.

A surgical innovation is defined as a quantum improvement in the treatment of a particular disease or group of diseases, and it usually is developed by an individual or a small group working together, said John Thompson, MD.

“The initial response is usually resistance from the academic community, and the innovators must endure criticism,” said Dr. Thompson, assistant professor of ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and associate clinical professor, University of Maryland, Baltimore. “The importance of their work often is not widely recognized for years after the initial description.”

While there have been numerous innovations that ultimately failed-such as retinal translocation and submacular surgery for choroidal neovascularization, among others-others have substantially improved treatments and achieved better outcomes over the course of time but were denigrated despite the fact that when properly executed with refined techniques, the medical peers refused to change the status quo.

There are countless such examples in the history of medical innovations, and one of the classics that Dr. Thompson recounted is that of the tortuous journey of Neil Kelly, MD, and Rob Wendel, MD, retinal specialists who wanted to address the treatment of macular holes in the mid 1980s.

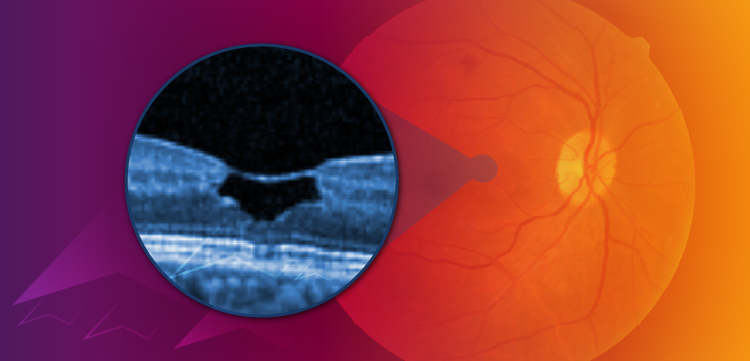

Dr. Kelly’s interest was piqued by the use of vitrectomy to treat impending macular holes and he thought that the surgery might be useful for full-thickness macular holes. After first failures, later cases were successful; Dr. Wendel observed in a failed case in which a retinal detachment occurred when the posterior hyaloid was left in place during the first surgery and later detached.

When the detachment was repaired, the macular hole closed and the vision improved, leaving the surgeons to think they were on to something, Dr. Thompson said.

“This also helped them realize the importance of the posterior hyaloid,” he emphasized.

Presentation of increasing numbers of cases at various meetings and submission of manuscripts to professional journals were met with hostility and skepticism.

However, they persevered, refined techniques, and increased the numbers of cases over time. In the early 1990s, their technique included pars plana vitrectomy, removal of the posterior hyaloid, peeling of the epiretinal membranes, a gas exchange 1 week postoperatively, and maintenance of a face-down position postoperatively. They reported in Ophthalmology a 73% macular hole closure rate and that 56% of patients gained three or more lines of vision.

At this point, the procedure was beginning to gain acceptance in the ophthalmic community and surgeons tried to modify the procedure. Some unsuccessful ideas to increase closure rates that were floated were use of small amounts of transforming growth factor-β2 applied to the holes, autologous plasma, and autologous platelet concentrates.

However, the controversy about macular hole surgery remained and a multicenter clinical trial was undertaken in 1997 to compare macular hole surgery with no surgery. The results showed marginally significant improvement in visual acuity, and the surgery was thought to lack benefit. However, at that time there were more complications and surgeon inexperience might have contributed to that conclusion.

At that time, longer gas tamponade times were favored and 16% perfluoropropane was found to be better than air in Dr. Thompson’s experience. A Japanese study then reported a 79% closure rate with use of 15% perfluoropropane and no face-down posturing, suggesting that many macular holes might close within a day or two and not require long-term tamponade.

Gas is preferred over silicone oil because of better visual results.

However, the optimal duration is controversial. The gas bubble must be large initially to maintain the tamponade effect. Over a period of 10 years, favor has shifted from perfluoropropane to sulfur hexafluoride. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed that most holes closed rapidly in a study that reported a 96.2% closure rate, but some required 7 days.

Ideas about prone positioning also have evolved. Most U.S. surgeons favor 5 to 7 days in a face-down position and few have abandoned that positioning entirely.

Internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling has also become essential and is associated with the highest rates of macular hole closure. Indocyanine green is favored in the United States for staining.

Macular hole surgery is associated with excellent long-term stability of the visual acuity, with 88% remaining closed longer than 5 years. In Dr. Thompson’s experience, he achieved 98% closure at 3 months with one surgery with improved vision at all time points from 20/160 to 20/63, with 61% gaining three or more lines, and 45% had 20/40 or better.

Recent advances in macular hole treatments are the inverted flap technique using Brilliant Blue-G as the best stain, intraoperative OCT to view ILM peeling, and use of an autologous retinal graft to close macular holes.

“Thanks to the initial work of Drs. Kelly and Wendel and many subsequent refinements by other investigators, the surgery is very successful for treating macular holes,” Dr. Thompson concluded. “Hundreds of thousands of patients have benefited from their work.”

Dr. Thompson is a consultant to Genentech Inc. He delivered the American Society of Retina Specialists’ Founders Award Lecture at the 2017 annual meeting in Boston.

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.