- Modern Retina Summer 2023

- Volume 3

- Issue 2

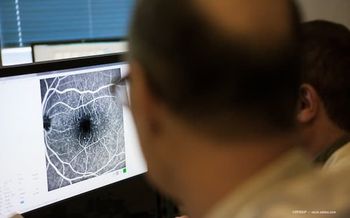

Experts detail innovative therapies for DME and neovascular AMD

New treatment options enhance patient visual outcomes and reduce treatment burdens.

Patients with diabetic macular edema (DME) and neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) are beginning to reap the benefits of treatment advances that prolong drug effects and require fewer injections. This article summarizes the highlights of these innovations and improved treatment strategies.

High-dose aflibercept for DME

The PHOTON study (NCT04429503) evaluated the safety and efficacy of high-dose aflibercept (Eylea; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals) for managing DME. David Boyer, MD, senior partner at Retina-Vitreous Associates Medical Group and adjunct clinical professor of ophthalmology at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, reported the results at the Angiogenesis, Exudation, and Degeneration 2023 virtual conference.1

Boyer explained that with the current management focus for DME on anti-VEGF therapy, the study design theorized that increasing the molar dose of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy might lessen the treatment burden, which was seen in a rabbit model. When introduced into clinical trials, an 8-mg dose, 4 times the normal dose, was injected in 70 μL of fluid into the eye, resulting in a longer time before the next treatment was required.

When the 8-mg dose was tested every 12 weeks and every 16 weeks, the results were noninferior to the current 2-mg dose administered every 8 weeks. The treatment burden was decreased considerably, according to Boyer.

The letter gains in vision were significant with the extended-dose regimen, and the safety profile was comparable to the 2-mg dose. The gains in vision were generally sustained, allowing most patients to stay on the treatment intervals every 12 weeks and every 16 weeks.

Incorporating faricimab in the real-world setting

David Eichenbaum, MD, director of research at Retina Vitreous Associates of Florida and collaborative associate professor at the University of South Florida Health Morsani College of Medicine in Tampa, explained that he tends to prioritize new drugs for patients who need more frequent injections with existing agents to achieve greater durability. He began using faricimab (Vabysmo; Genentech) in treatment-naïve patients soon after its commercialization because the phase 2 and 3 trials did not identify adverse events.

“I’m test-driving it [with] treatment-naïve patients to see [whether] it works as in the TENAYA [NCT03823287], LUCERNE [NCT03823300], YOSEMITE [NCT03622580], and RHINE [NCT03622593] trials. I’m using it in patients who haven’t achieved a bearable extension or sufficient dryness using established antiangiogenic agents. Because the retinas of some patients with diabetes stay wet with the current agents, I use corticosteroids, but they are not well suited to all patients,” Eichenbaum explained.

Eichenbaum is also trying to achieve better efficacy in the patients with slightly wet diabetic edema who have treatment experience. He wants to establish longer treatment intervals in treatment-experienced patients with relatively dry and wet AMD whose treatment cannot be extended in the real world. In the treatment-naïve population, he is

testing personalized treatment intervals with 4-week extensions to attempt to duplicate the clinical study data, including load and extension phases.

Caroline Baumal, MD, professor of ophthalmology and director of retinopathy of prematurity service at New England Eye Center, Tufts Medical Center, in Boston, Massachusetts, looks at patients who have responded well to previous drugs before faricimab but who want longer durability. She may try faricimab in patients who have not responded completely to see whether there is an additional angiopoietin-2 (ANGPT2) effect, and she relies on the results of the clinical trials. She has treated numerous treatment-naïve patients with faricimab and is pleased with the results so far, although she notes that these results are early in the treatment process (after only a few injections).

Eichenbaum explained that in practice he switches patients to

faricimab without recommending a medication washout. He does not duplicate the treatment regimen of the clinical trial population in treatment-experienced patients, but in treatment-naïve patients, he follows the clinical trials. The TRUCKEE trial showed some limited real-world data with 1 injection, but the safety data after 1 injection suggested some improved efficacy.

Mode of activity of faricimab

Baumal cited the faricimab preclinical data, which supported the finding that the ANGPT2 effect caused increased durability of VEGF inhibition. The diabetic data indicated that there are some optical coherence tomography–driven data showing that patients with diabetes have drier disease. A dual mechanism is likely instrumental in the durability in AMD, which will be clarified over time.

The long-term extension trial, AVONELLE-X (NCT04777201), of the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials, will ultimately provide a 4-year data set. In addition to durability, findings from the extension study will shed light on long-term safety, according to Eichenbaum.

Regarding the diabetes data set, the drug’s activity in diabetes might speak more to the dual mechanisms of action or the additional mechanism of ANGPT2 inhibition, Eichenbaum noted. In the second year of the YOSEMITE and RHINE trials, an increased proportion of patients achieved extended treatment interval in DME. He wondered whether that combination with the early anatomic suggestion of superiority in the first year of the YOSEMITE and RHINE trials suggests that the dual mechanisms of action may be more apparent in DME.

The advantage is that 1 dose of faricimab can be used to manage 2 different diseases compared with ranibizumab (Lucentis; Genentech), which uses 2 different doses for AMD and DME. “A single dose makes faricimab easier to use and track,” Baumal said.

Implications of treat-and-extend dosing in AMD

In the phase 3 AMD clinical trials of injectable therapies, 60% of

treatment-naïve patients in the TENAYA and LUCERNE trials were treated every 16 weeks. Nearly 80% of the patients could be treated every 12 weeks or longer, which decreased the injections to 10 compared with 15 with aflibercept. “[These were] the first data that showed noninferiority to every-8-week aflibercept, which is an outstanding gold standard regimen with significantly longer intervals and a significantly reduced mean number of injections,” Eichenbaum said.

Baumal pointed out the advantages of the study design, in which patients in the faricimab arm received 4 monthly loading-dose injections. Patients were stratified based on disease activity assessments at weeks 20 and 24. Based on the retinal status at that time, treatment was every 8, 12, or 16 weeks. This study identified patients who needed more frequent treatment. “If you had disease activity at week 20, you were treated every 8 weeks. You were identified as someone needing more injections. If you didn’t have disease activity at weeks 20 and 24, you were in the every-16-week arm,” she said.

At week 60, patients began a personalized treatment interval until week 112. This identified patients who needed more frequent treatment for the first 60 weeks. After that, they entered a more protocol-driven, treat-and-extend regimen, which is similar to real-world practice. “Looking at the faricimab arms, I’m very encouraged that the median number of injections [were fewer]. If we can tell our patients, based on how they respond in the beginning, where they might fall after 2 years, that will be encouragement for our patients,” Baumal said.

Treatment selection and shared decision-making in AMD and DME

Durability, patient approach, and patient preferences regarding injection frequency are important factors. For Baumal, safety is a major factor considering the potential for inflammation and occlusion vasculitis with injected treatments, especially in a population with diabetes.

However, the shared decision-making is not always about medication. Patient education about their disease is extremely important to Eichenbaum. Spending time with patients will result in improved treatment adherence. Shared decision-making combined with scientific knowledge will produce the best results for patients.

In addition, patients want to know how their lifestyle will be affected, the odds of having an adverse event, and the positive effects of treatment. “It’s nice to have confidence when you’re helping them through this process of shared decision-making and the agents that you’re recommending. It’s a huge benefit of those agents,” Eichenbaum said. Building trust in the patient relationship is a key part of the shared decision-making process.

“Using these medications in the real world poses a different set of issues than in the regimented clinical trial protocols,” Baumal said. For example, how a treat-and-extend regimen is structured depends on the prescribing physicians; some use 2-week intervals and others use 4-week intervals. In addition, administering monthly injections and as-needed injections can mean different things.

Based on this, Baumal advised physicians to set expectations for patients. She tells patients about the need for frequent treatment during the first year to achieve a dry retina. Over time, patients will typically need fewer injections, but this varies based on the patient response.

AMD, DME, and quality of life

Wet AMD and DME affect patient quality of life. The advent of anti-VEGF therapies has mitigated that somewhat. However, patients are

still affected.

Even though AMD and DME are different diseases affecting different age groups, they affect patients similarly. “The diseases affect their ability to drive, read, and be independent, especially with advanced disease. Because of that, we know how important vision is and the fear of loss of vision that happens in young patients, who need it for their ability to work, and in older patients, who need their vision to stay independent. The impact is huge, and for our patients, nothing is as important as their vision,” Baumal said.

The quality-of-life implications have improved markedly with

anti-VEGF therapy. With good treatment, the quality-of-life improvements are profound. Previous to that, patients with AMD had no options.

Because of anti-VEGF treatment, patients are presenting earlier with the potential to preserve more vision. The next issue is the burden of treatment.

Unmet needs in AMD and DME

Eichenbaum pointed out that patient representation in clinical trials needs improvement. The phase 4 study ELEVATUM (NCT05224102) is evaluating faricimab in a population of patients who self-identify as Black, Hispanic/Latin American, or Native American/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander in addition to Asian Indian participants from India. This type of inclusive trial will improve equity and provide a data set from patients that matches the real-world population.

To that end, Baumal strives to find the right balance of seeing patients less frequently, monitoring, and administering injections safely. “If an agent lasted 3 to 4 months, that would be ideal. I still want to see my patients. I want to check their retina. I want to make sure they don’t have any other coexisting diseases. The availability of home optical coherence tomography will fill a monitoring gap between treatments,” she said.

She also pointed out that the ELEVATUM study looked at patients who do not meet clinical trial criteria for systemic parameters or those who cannot undergo monthly checkups needed in a clinical study. She hopes that the study will provide a better idea of how these patients will do in a real-world treatment setting.

Eichenbaum would like to have a treatment other than faricimab that improves durability and efficacy. “We have some of those agents in the pipeline in clinical development, and there’s a lot of excitement for things [such as] gene therapy and the port delivery system.” However, he noted that safety remains of the utmost importance. His “dream agent” is not yet in the pipeline. •

REFERENCE

1. Angiogenesis, Exudation, and Degeneration 2023 — Virtual Edition. Efficacy and Safety of high-dose (8 mg) Aflibercept for Treatment of DME: 48-week Results from PHOTON. Bascom Palmer Eye Institue. February 10, 2023. Accessed June 14, 2023.

Articles in this issue

over 2 years ago

Study finds significant variance across imaging modalitiesover 2 years ago

New VEGF trap for wet AMD takes aim at VEGF-C and VEGF-Dover 2 years ago

Is complement therapy the path forward for geographic atrophy?Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.