NMA 2024: Pearls for managing melanocytic ocular surface tumors

Kathryn Colby, MD, PhD, described diagnosing and managing these tumors at the National Medical Association annual meeting, Ophthalmology Session in New York.

Reviewed by Kathryn Colby, MD, PhD

Melanocytic ocular surface tumors are serious and potentially life-threatening lesions that require appropriate management to achieve the best prognosis. Kathryn Colby, MD, PhD, described diagnosing and managing these tumors at the National Medical Association annual meeting, Ophthalmology Session in New York. She is the Elisabeth J. Cohen Professor and Chair, NYU Langone Department of Ophthalmology, New York.

Case report

She described the case of a 42-year-old Hispanic man who had been referred for a suspicious ocular lesion that increased in size during a 4-month delay in presenting for a consultation. Following excision, the patient underwent cryotherapy and ocular surface reconstruction. The pathologic evaluation revealed invasive melanoma; however, the patient declined adjuvant topical chemotherapy and an oncology referral.

The subsequent follow-up was inconsistent and the patient was lost to follow-up. Six years later, he presented again. There was no local recurrence of the melanoma, and the eye was stable, but multifocal metastatic disease had been diagnosed.

Dealing with conjunctival melanoma

This lesion, which resembles skin melanoma, does not develop often, but the incidence may be increasing, according to Carol Shields, MD, and colleagues, who reported that at the 10-year time point, 51% recur, 26% are metastatic, and 13% of patients had died.1

Conjunctival nevi may be the precursors of some of the ocular tumors. The nevi generally develop in the interpalpebral fissure at the limbus; the nevi may be amelanotic, often contain cysts, and may grow during puberty.

“Up to 25% of melanomas arise from pre-existing nevi, so they need to be watched and removed if changes are documented,” Colby stated.

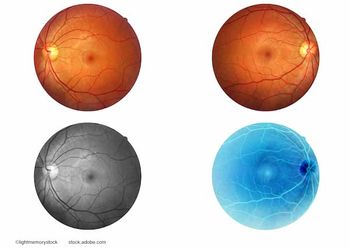

Considering the diagnosis of melanocytic ocular surface tumors, she advised that they have many different looks, some quite obvious and others subtle.

Conducting the examination

She provided the most important factors to consider during the examination. These include:

- Palpation of head and neck lymph nodes

- Complete evaluation of all conjunctival surfaces, including the upper fornix

- Determining if the lesions are mobile or fixed and

- Identifying increased vasculature

Colby advised that the differential diagnosis consider benign acquired melanosis. This is defined as bilateral ill-defined flat pigment that is present in pigmented patients. The pigment is more prominent at the limbus and in the interpalpebral fissure and fades toward the fornices. Colby advised clinicians to beware of isolated pigment in the fornix or on the palpebral conjunctiva.

She also discussed primary acquired melanosis (PAM), a flat pigment with irregular margins that develops in middle-aged or elderly white patients. Most melanomas originate from PAM; cellular atypia is the main prognostic factor. Currently, atypia can only be determined by biopsy.

“Some, but not all, PAM with atypia progresses to invasive melanoma, ie, 36% to 75%,” she reported.

However, not all cases of PAM with atypia are the same: some carry a low risk of progression to melanoma with a good prognosis and others a high risk with poor prognosis.2

Colby explained that topical mitomycin C (MMC) can be useful in cases of diffuse PAM with atypia.3 However, MMC comes with a menu of adverse effects: conjunctival injection, acute toxic keratitis, contact dermatitis (pre-septal cellulitis), uveitis, glaucoma, scleral melt, cataract, and persistent epitheliopathy likely due to limbal stem cell damage.

Recurrent melanoma

These lesions are often amelanotic, despite that the primary tumor might have been pigmented. Colby’s pearl is that any pigment or mass lesion in a patient with a history of conjunctival melanoma is considered recurrent melanoma until proven otherwise.

“When managing conjunctival melanoma,” she said, “this is a surgical disease. Appropriate management improves the prognosis. Treatment includes the combination of surgical excision, cryotherapy, and adjuvant topical chemotherapy.”

Long-term Management of Conjunctival Melanoma

Patients require close follow-up indefinitely, because the tumor can recur even decades later. Systemic screening can be done by an oncologist, but the optimal regimen is not well-established, because of the rarity of conjunctival melanoma. Finally, any recurrent pigment or mass lesion should be assumed to be malignant until proven otherwise. When in doubt, a biopsy with cryotherapy. should be performed.

Commercially available genetic testing is currently available that may help guide therapeutic decisions and inform the prognosis. The potential therapies include small molecules and immunotherapy.

Circulating cell-free DNA may be a helpful adjunct to detect recurrence/metastasis.

References

Shields CL, Shields JA,

Gündüz K, et al. Conjunctival melanoma: risk factors for recurrence, exenteration, metastasis, and death in 150 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1497-1507; doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.11.1497.Sugiura M, Colby KA, Mihm MC, et al.Low-risk and high-risk histologic features in conjunctival primary acquired melanosis with atypia: clinicopathologic analysis of 29 cases. Am J Surg Path. 2007;31:185-192;DOI: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213339.32734.64

Colby KA, Nagel DS.Conjunctival melanoma arising from diffuse primary acquired melanosis in a young black woman. Cornea. 2005;24:352-355; doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000141229.18472.a2.

Colby K. Management of Melanocytic Ocular Surface Neoplasia. Presented at the National Medical Association annual meeting, August 3, 2024, in New York. Session: Cornea/Dry Eye Symposium

Newsletter

Keep your retina practice on the forefront—subscribe for expert analysis and emerging trends in retinal disease management.